Where faith and optimism intersect

Faith fuels the revolution of the masses, while religion washes it down the drain.

The following post is an article divided into three parts- the first of which is a personal essay; the second, a critical study of various texts; and the third, an interpretation of the Hindi film Anand- interwoven to emphasise the subject at hand. Feel free to jump to the section that interests you the most. It is however strongly recommended that you read the entire article in the prescribed sequence.

At one point in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Anand (1971), Dr. Bhaskar Banerjee (Amitabh Bachchan) finds himself compelled to believe in a God, in spite of being an atheist, as some sort of a last resort of hope that his terminally ill friend, Anand (Rajesh Khanna) survives.

I first watched Anand last year when I found myself struggling to socialise with my peers. The film became an instant favourite. It follows its titular character, a cancer patient with numbered days, and how he lives them to the fullest, while giving the timeless message of optimism and finding joy in little things. Predictable yes, but I ate it up at the time. As someone who easily gives in to pessimism at the slightest inconvenience, Anand sort of became the light at the end of the tunnel for me, and as corny as it sounds, gave me the strength to overcome my fears. Rewatching assorted clips from the film on my phone became a morning train ride ritual. But just like everything else, it eventually fell out of habit, and life went on, inviting new conundrums and misadventures.

During this interval, I became immensely radicalised and started getting heavily involved in left-leaning revolutionary work. My own shortcomings in life drove me deeper into politics, further leading me to translate learnt theory into everyday praxis. Subsequently, spending money on buying little treats after class was replaced by chipping in mutual aid instead. The pop culture art I spent hours drawing on my phone had grown off me; now I drew art depicting socio-political issues. Watching mainstream movies on the train for leisure was a thing of the past— I had now started watching “deep,” “serious” documentaries that reflected society and talked about “important” subjects. Every Instagram story I came across talked about the evils of the world— some of them I was a part of already, but was only now beginning to comprehend.

Needless to say, reminding yourself of all the suffering in the world at every minute of your life gets taxing after a point, especially when you’re not in a position to fix the world by yourself. And so, there I was, spiraling back into chronic defeatism.

My country was on a similar path: India has been on a downward spiral for quite some time too. While its descent into Hindu right-wingism didn’t start with the Ayodhya Ram Temple installation1, at some level, that was the incident that really stirred something in me. Full privilege disclosure: I belong to an oppressor-caste2 Hindu household, and even though my family wasn’t cheering on to the growing Hindutva fear mongering in the country (thankfully), there was a voice in my head that kept telling me that I was a part of the problem. That the “liberatory” work I was doing clearly wasn’t enough, because at the end of the day, I was still on the oppressor’s team— not by choice, but by birth. My existence and my fate was sealed with the fascist’s side for eternity.

I don’t ever remember taking my religion seriously, except for a brief mythology phase in the seventh and eighth grade. I used to wear a bracelet from Mangueshi, Goa- my family’s native-slash-religious place- on my right wrist, not because I was a part of a fanatic cult, but simply because it looked aesthetically pleasing. I got rid of it. All of a sudden, I started getting rid of everything religious injected in my mind and bestowed on my body at an early age. I had started introspecting and self-reflecting. I had started reading anti-caste texts, following Ambedkarite organisations, and somehow on the road to enlightenment, I had started abandoning my “religion,” one step at a time. The religion that perhaps I never really liked in the first place but didn’t get particularly bothered by either. The religion that I merely tolerated for 19 years of my life.

My “oppressor” identity weighed on my shoulders like a heavy burden. It was in my mind at all times, still is to a certain level. Religious guilt isn’t something easy to get rid of, especially when you have spent 19 years as its progeny, and it manifests in your reality with every saffron Jai Shree Ram flag you see in your locality. My religion (and caste) gave me a voice and privilege in a deeply flawed, deeply problematic society. Sitting on top of an inherently unequal and tyrannical system, albeit without my choice, ended up making me the oppressor too, no?

I don’t want to spend this entire blog post wallowing in self-pity. I’m lucky enough to say that my family never really forced anything on me. I could just opt out of my religion at any given point, and they would still treat me with the same love and affection. But unlearning something you have spent approximately two decades with comes with its fair share of challenges. There is still a trail of guilt and uneasiness lingering at the back of my mind as I type this out. I was in a strange, strange dilemma, where I knew I had considerable privilege in society because of my identity, but felt undeserving to enjoy the fruits of that very privilege. The vices of self-hatred and defeatism were taking over me at the ripe age of 19— an age they depict in movies as the pinnacle of youth and exuberance and whatnot. Here I was, wasting away that youth with the recurring question whirring inside my head like the cantankerous clashes of metal cymbals: have I become an atheist?

***

My mode of thinking is largely inspired by the Left. Western radicals have routinely criticised organised religion and encouraged atheism. In his essay Socialism and Religion, Lenin describes religion as “one of the forms of spiritual oppression which everywhere weighs down heavily upon the masses of the people, over burdened by their perpetual work for others, by want and isolation.” He goes on to say that socialists, are by default, atheists— they follow no religion. Trotsky, on the other hand, declares in Problems of Everyday Life that religiousness does not exist in the Russian working class at all, and that they only follow the Church out of habit and daily custom. While I do agree with the criticisms against religion by these respected leftist figures, I can’t bring myself to apply the same to the idea of faith. To me, faith and religion are two completely different things. Faith is innate, while religion is ascribed. Faith is a proponent of humanity, while religion is a learnt and rigid systemic structure that you either are born in, or voluntarily choose. Religion is external, but faith is internal.

Moreover, these criticisms, for the most part, apply to occidental religions— more precisely, the relationship between the state and the church. I live in a country where a) Catholicism falls under a minority, b) The dominant religion is Hinduism, which I don’t think fits the template of an “organised” religion in any shape or form; it is more so a loose collection of rituals and traditions stitched together from various communities, and c) The dominant religion is built upon the hierarchical caste system, which isn’t a common denominator in any other religion. I needed a solid criticism against my religion to absolve me of my religious guilt. It came to me in the form of Ambedkar.

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, fondly referred to as Babasaheb, was a renowned political leader, widely known for authoring the Indian Constitution. He was born in a Dalit family- the lowest rung of the Hindu caste system- and faced caste-based discrimination all his life. The brutal oppression he faced channeled a deep-rooted resistance in him, against the dictatorial religion, which resonated with large numbers of his caste-oppressed followers, igniting a legendary anti-caste fight throughout the Indian subcontinent. Babasaheb remained a staunch critic of Hinduism all his life, but unlike his Marxist contemporaries, he did not oppose the notion of religion itself— he still acknowledged religion’s place in life. “Religion is a very necessary thing for the progress of mankind. I know that a sect has appeared because of the writings of Karl Marx. According to their creed, religion means nothing at all… I am not of that opinion.”3

The constant tug-of-war between Indian Communists and anti-caste radicals forms the crux of the Indian Left. Anand Teltumbde writes in his book Anti-Imperialism and Annihilation of Castes that in order to overthrow capitalism, and subsequently, imperialism in India, one should understand the complex veins of caste system in addition to the class system in the country, which isn’t typical of Western society that Western ideas of Communism were modeled on. Indian Communists frequently sidelined the issue of the caste system, blaming it on the “super-structure” rather than the foundation itself, leading to persistent conflicts with Ambedkarites. Marxists claim that religion was the opiate of the masses; however, in a country where the lowest tier of society is oppressed precisely on the basis of religion, this statement becomes hard to stand by. Western Communism was not going to work in India without specific tweaks in order to deftly apply to the country’s inexorable caste system.

It is worth noting, however, that the Indian Left did start taking the issue of caste into consideration in due time. Moreover, Ambedkar himself was documented to be confessing that parliamentary democracy was not going to work in India because of the social structure of caste, and prescribing “some kind of Communism,” as an alternative, in a later recording.4

“The movement to leave the Hindu religion was taken in hand by us in 1955, when a resolution was made in Yeola. Even though I was born in the Hindu religion, I will not die in the Hindu religion. This oath I made earlier; yesterday, I proved it true. I am happy; I am ecstatic! I have left hell — this is how I feel. I do not want any blind followers. Those who come into the Buddhist religion should come with an understanding; they should consciously accept that religion.”

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar

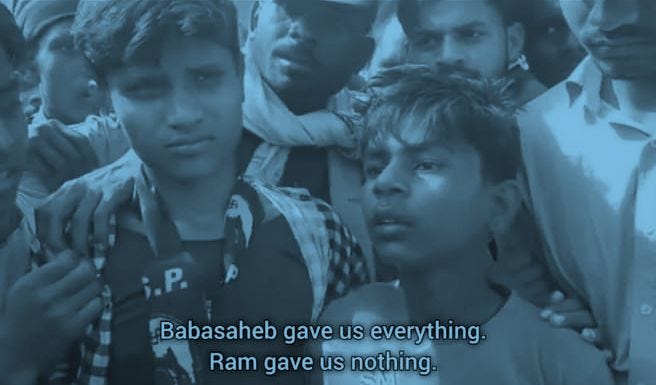

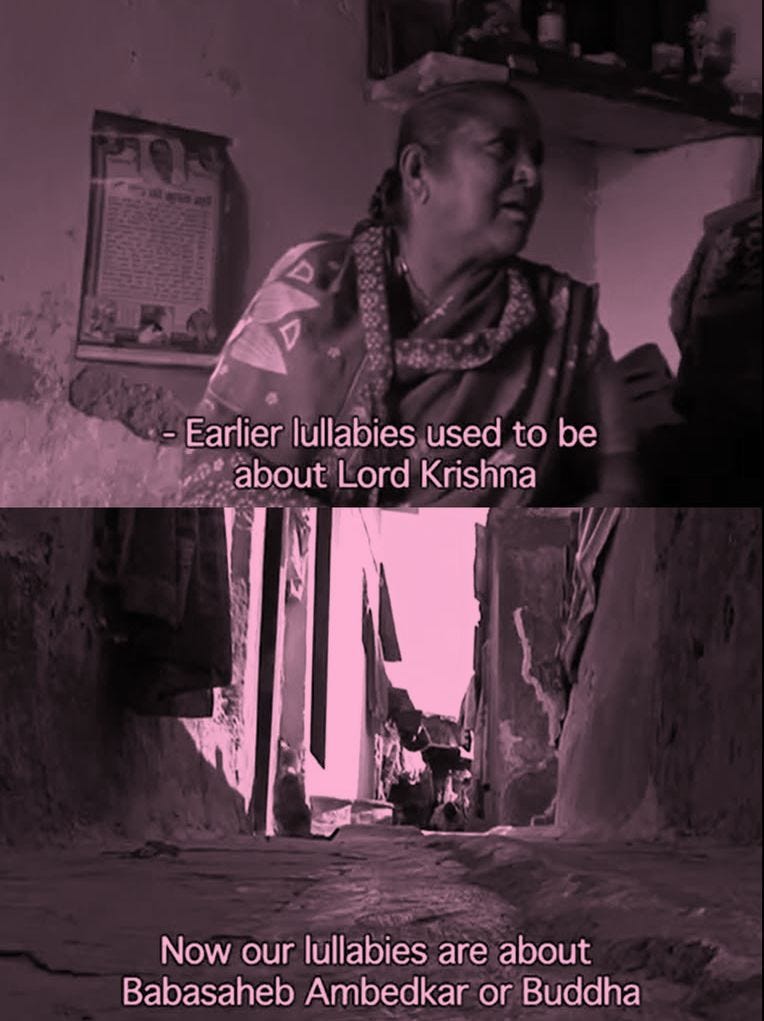

On 14 October 1956, Ambedkar embraced Buddhism at Deekshabhoomi, Nagpur, thereby renouncing Hinduism. Today, thousands of Ambedkarite Buddhists continue to walk on his path. It is worth noting that while they refrain from worshipping traditional Hindu deities and giving in to that religion, their faith remains intact: it stays alive in the memory of Ambedkar and the Buddha. A heartwarming scene from Anand Patwardhan’s seminal anti-caste documentary Jai Bhim Comrade (2011) spotlights a poor caste-oppressed woman elaborating on how her community replaced singing folk lullabies about Hindu deities like Krishna with those about Ambedkar and Buddha.

Their faith did not go away with the religion. It simply shifted to a new vessel: a new flame to keep their hopes alive.

***

I was back to square one, retiring to the shadows of pessimism. This enabled me to rewatch Anand a couple weeks ago— just like the good old days, when my only problem in life was not having enough friends. Simpler times.

My obvious takeaway from my initial watch of Anand was a preliminary surface-level reading of the film: one should live their life to the fullest no matter how bad it gets, find happiness in the little things, all that jazz. But my recent rewatch revealed something greater; I discovered there was more to the film. Specifically, with Bhaskar Banerjee, or “Babumoshai” as he is referred to, who I didn’t necessarily pay attention to in my former viewings.

Bhaskar is a young idealist, visibly depressed at the poverty and illnesses plaguing the country. He is disillusioned and pained to see the distress of the masses, which culminates into his dissatisfaction as a doctor: sure, he can treat patients back to health, but there is no cure for the rampant poverty, the endless suffering around him. How can he prescribe medicines to those who cannot even afford a day’s meal? Bhaskar’s disappointment in the world crystallises into self-loathing and alienation. He is mad at the system, but has no void to shout into. He feels that he is not doing enough, often drowning in pessimism and solemnity. He has no family, and very few friends— two of whom include his house help Raghu Kaka (Dev Kishan), and his fellow doctor Prakash Kulkarni (Ramesh Deo). Bhaskar single-handedly takes systemic failures upon his sole shoulders leading him to develop a defeatist attitude in life. Ring a bell?

You can’t solve a systemic issue by yourself. Friedrich Engels, in The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845), calls starvation, impoverishment, and lack of proper nourishment a “social murder” that the entire society is guilty of. Still, I was in the same shoes now that Bhaskar Banerjee donned way back in 1971. How can you be cheerful and optimistic in such a messed up world? What does it mean if you are happy in such a deeply problematic society? What is there to truly even smile about? We live in a world where living a quote-unquote “normal” life has become a privilege. Having access to basic necessities like food, water, clothing and shelter, as dystopian as it sounds, is a privilege, in a world where people are bombed for the mortal sin of existing. While on one hand, being aware of this extensive privilege has made me more grateful about the little things in life, it had also made me incredibly dejected, like Bhaskar.

In comes Anand, the eponymous happy-go-lucky cancer patient from Delhi thinly balancing himself along the jaws of death, who wishes to spend the rest of his short-lived life in Mumbai with Bhaskar and his friends. Perhaps there is a heightened sense of urgency to indulge yourself in as much as you can when you know something is short-lived. Or perhaps, it was simply the fact that Anand- a child of the Indo-Pak partition- had lost everything, from his family to the love of his life to his steadily deteriorating health, that had prepared him for the worst. Either way, Anand’s exuberant outlook and zest for life predictably transforms Bhaskar, paving way for optimism in his life. But Anand isn’t the only sliver of hope in Bhaskar’s otherwise dreary life. It’s also faith. Faith that his peers subscribe to, as their only bridge to optimism.

Where do you find God? You find God among the weak and disempowered. You do not find God among the rich. You do not find God among the powerful, the smug, or the arrogant. You find God among those who suffer in life. God stands side by side with them to bear witness as to whether you, as an individual, realize that the balance of rights and duties obligates you to act in such a way.

From "The Qur'an, the Sunna, and the Intellect" The Prophet's Pulpit: Commentaries on the State of Islam, Volume III

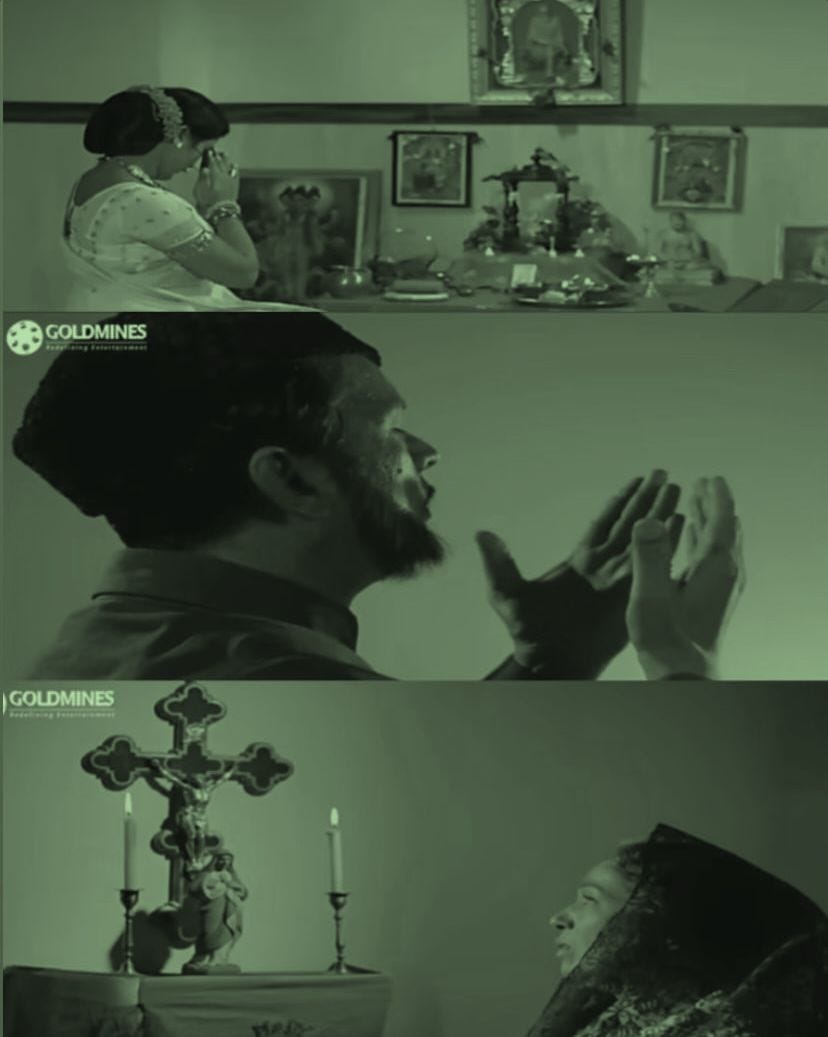

There is a brief montage near the climax which features different characters praying to different deities to save Anand’s life. Prakash Kulkarni’s wife, Suman (Seema Deo), is a devout Hindu, who is regularly seen chanting verses in front of her deities, pleading her God to save Anand. Ms. D’sa (Lalita Pawar), the Catholic matron, kneels in front of the cross, while Isabhai Suratwala (Johnny Walker), the Muslim theatre artiste, submits himself to Allah for the same cause. Raghu Kaka even plans to visit his native place because he has faith in his family deity that Anand will be saved.

He has faith.

When all else fails, faith continues to burn on. You can see the film’s ending coming from a distance: none of these things actually work, and Anand does, in fact, pass away. But these instances of community effort of faith, despite religious differences, leave behind the subtle essence of solidarity, love, and positivity in the face of fear. Faith may not be rooted in scientific materialism, but it is unflinchingly rooted in optimism. Faith may not be concrete and rational, but it can be humane and emotional. All critiques against organised religion aside, the human mind begs to believe in a higher power sometimes, just as a balm to comfort oneself that certain things are out of their control. Looking up to that higher power gives them a reason to continue being hopeful. There is a reason why even the least religious of us chant a quick prayer in our head before commencing the exam. There is a reason why even a haughty-taughty atheist like Bhaskar was compelled to believe in a higher being later on in the film. In times of hardship, it is easier to force our mind into letting go of control and letting a mythical higher being take on from there— letting a little responsibility escape our autonomy.

'Belief' softens the hardships, even can make them pleasant. In God man can find very strong consolation and support. Without Him man has to depend upon himself. To stand upon one's own legs amid storms and hurricanes is not a child's play. At such testing moments, vanity —if-any— evaporates and man cannot dare to defy the general beliefs. If he does, then we must conclude that he has got certain other strength than mere vanity. This is exactly the situation now. Judgment is already too well known. Within a week it is to be pronounced. What is the consolation with the exception of the idea that I am going to sacrifice my life for a cause?

Bhagat Singh, Why I Am An Atheist (1930)

I may not subscribe to any religion (I’m on my quest of learning about as many religions as I can, though), but I do not think I’m going to stop having faith either. I may rant and complain about having privilege now, but by denying the existence of a higher being, what am I doing? Denying the vulnerable and marginalised sections off of the one thing they look up to in their times of hardship? It’s been more than a year since the ongoing genocide in Gaza, and everyday I have Palestinians reach out to me for help. On most days, I scrape out my measly earnings and pour them in their GoFundMes, and they bless me in return, saying that they hope that Allah looks after me. Allah is hope’s second name for them. What do I gain by announcing that I do not believe in the only thing that replenishes them with hope day after excruciating, agonising day? What do I gain from cutting off the one thread of hope that they are desperately clinging on to?

Don’t get me wrong: religion has always come packaged in a stark power imbalance, and religion in the hands of the oppressors has always been catastrophic. The number one reason behind the world’s greatest man-made calamities is ethno-religious differences. For every new headline about Sanghis5 suspecting a new temple beneath an age-old mosque6, prompting their clueless followers to demolish it, there is an example of religion joining hands with fascism. For every grand temple inauguration in a country where an alarming number of people still live below the poverty line, there is an example of religion joining hands with political malice. And for every multi-millionaire spending millions endorsing religion on their over-the-top wedding sequences smack dab in the middle of the country’s financial centre, overlooking demolished settlements owing to their residents’ socio-economic conditions, there is an example of religion joining hands with capitalism.

But faith? Faith drives resilience. Faith pervades through the unimaginable. Religion in the hands of the ruling class is a weapon against the vulnerable; faith in the hearts of the working class is a band-aid to the oppression of the higher-ups.

Works cited in this post:

Anti-imperialism and Annihilation of Castes- Anand Teltumbde

The Condition of the Working Class in England- Friedrich Engels

"The Qur'an, the Sunna, and the Intellect" The Prophet's Pulpit: Commentaries on the State of Islam, Volume III

I’ve been going back and forth on the idea of a paywall for a minute now. I do not like the concept of a paywall. I’m not judging anyone who has one- I get where you’re coming from and your labour absolutely has to be compensated for- but I feel like that’s just not me. There have been times when I have wanted to read an article only to find out with a dejected face that I need my card and a monetary sacrifice to unlock it. Of course at some point my trajectory of thinking might change as it always has, and I might introduce a paywall, but for now, The Untelevised Revolution is going to remain free for everyone- subscribers and trespassers alike. (Also, putting a paywall with a name like “The Untelevised Revolution”….. yeah.)

THAT BEING SAID, I’m really falling short of money right now and I’m looking at pretty much every option available to help me financially. I know I don’t have a lot of subscribers, but if you did enjoy reading any post of mine at any point and are in the position to help financially, please do so I’d be super grateful to you. To many more.

Caste explained: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-35650616

Slang for members of the Sangh Parivar, a right-wing Hindu nationalist movement

Officially the best thing I’ve read in a long, long time, sorry it took so long but you deserve your flowers. Incredibly written, so proud (“:

These topics being my subjects as well as my caste I have been reading these books since long. Especially Anand Teltumbde And Suraj Yengde , two of the bwst writers currently on the conversation, I am deviating sorryyy. This was sooo Good!!!! I also recently watched Anand . And you have brought this all together in a great way.

Religion, being not of that importance to me is still a point of struggling confusion , for me . Looking Forward to the next two articles.