Neither Culture Nor Class War, But A Secret Third Thing

Forget separating the art from the artist– can you divorce the art from the context it was made in?

Privilege disclosure: I’m a 20 year old Konkani-speaking cisgender Savarna woman residing in Mumbai. I have never faced caste- or religion-based discrimination in my entire life, so maybe I’m not the best person to write on this topic, but I did have a lot of things to get off my chest, resulting in this post. I suggest approaching this essay with a critical lens.

This is largely a personal essay about unlearning social conditioning and exploring systems of oppression on my own. I realise that through posts like these I risk centering myself in conversations I do not belong in, and if you genuinely do want to learn more about casteism, you should start reading works by marginalised caste-oppressed people firsthand, instead of relying on a blog post by an urban Savarna woman. Accordingly, I have included a list of works by important anti-caste writers at the end of the post. I hope this blog post leaves you with intriguing topics to ponder about, instead of an insatiable urge to cuss me out for triggering your religious sentiments and raising important conversations.

I happened to catch a theatrical performance in my native place of Ponda in Goa, back in December last year. The talented all-female crew was performing a popular Marathi Sangeet Natak (musical), a cultural cornerstone whose songs I had incidentally grown up on. In spite of hailing from a Konkani-speaking family, I grew up listening to my Grandpa enthusiastically sing a wide variety of Marathi songs– from classical and semi-classical works from well-known Sangeet Nataks, to folk songs, to devotional abhangas, to commercial film music. Grandpa’s vast inventory of Marathi music usually manifested in real-time when he immersed himself in a solitary in-house baithak with his harmonium, or simply hummed along to one of his favourite tunes by himself, lying down on the living room couch.

As soon as the first few notes of the lead song came on in the play, I vividly felt goosebumps crystallising on my skin. Indulging in faded nostalgia is one thing, but experiencing the said nostalgia within the context of its original creation is another. And with everything said and done, the song is a brilliant piece of artistry in itself, wielding an impeccable level of skill and musical expertise. The dream-like lull of the harmonium, with the steady pacing of the tabla, and the mystical vocals pulling through just in time. Art is subjective, but one would be hard-pressed to deny the sheer mysticity of the song.

Until my moral and political conscience came cascading down on me. The song I was heaping praises on all this time is, but, a product of Brahminical hegemony. A casteist supremacy that has plagued Maharashtra’s rich and varied cultural heritage; an incorrigible stain on an otherwise stellar artistic legacy.

“Marathi theatre was an arena of the foremost significance for the negotiation of upper-caste cultural dominance over middle-class Maharashtrian identity” Veena Naregal explains in her research paper, Performance, caste, aesthetics: The Marathi sangeet natak and the dynamics of cultural marginalisation.1 She recounts Marathi theatre’s humble origins with supposedly “lower” art forms like the Lavani and the Tamasha- their lower status inscribed by the rigid and exploitative Hindu caste system- and the air of eliteness donned by the “superior” Sangeet Natak. Started by Balwant Pandurang “Anna” Kirloskar, the Sangeet Natak has largely featured and been of interest to upper-caste Maharashtrian elite, and has been routinely counted in the ranks of Indian high culture. Moreover, these musical plays generally revolved around chapters from Hindu mythology, which possess a Brahminical tinge in their own way.

Thoughts clouded my head as I walked out of the auditorium. I am not going to conceal my caste privilege. Even though I’m openly non-religious and anti-caste- both in theory and praxis-, I cannot deny that I have been able to enjoy and appreciate the fruits of the so-called high culture of western India, simply because my ancestors were born in a specific social setting, and probably even prided over their oppressor status, perhaps even gatekeeping this art from their peers born on the wrong side of privilege.

If you have read my previous post, you already know the heavy religious guilt I have been battling for quite some time now. This experience only worsened it. Did I have a right to enjoy an art form, even after knowing its problematic origins? And if I did, would that make me a hypocrite? Would that make me as bad as those who directly oppress the marginalised? Do I forcibly change my opinions on an art form, simply to show my anti-caste stance? Where would my free will as an art enthusiast lie then?

Or more importantly: was my free will as an art enthusiast really more important than the lives of caste-oppressed individuals, who have suffered endlessly at the hands of the same people who have birthed such exquisite art?

I’m not native to Maharashtra, even though I was born and raised here, in a standard Maharashtrian social setting. So perhaps, the hurt and disappointment I was experiencing was coming purely out of nostalgia, and not because of some innate cultural guilt. But how long can even my own culture be immune to anti-Brahminical critique? I may belong to a different ethno-linguistic group, but that does not erase my oppressor caste status. The oppressor caste that has unknowingly percolated into everything around me– the music I grew up listening to, the countless gods aligned at different spots in my house, even the food that I fondly consume.

Many months before my Goa trip, I remember trying to decode the origins of Phodi, one of my favourite cultural dishes that I grew up eating. Phodis are fritters made by roasting root-, shoot-, and fruit-vegetables, coated in a delectable assortment of spices. Again, my love for Phodi is inextricably linked to my Grandpa, who used to lovingly make them every alternate day for me as a child, and continues the tradition to this day.

It did not take me long to find out that my favourite childhood dish was considered an integral part of GSB (Goud Saraswat Brahmin) cuisine. Whether or not it is an original creation, or also a cultural appropriation from another community, is up for debate.2

Something shifted in me as soon as I found this out. Call it my ingrained caste privilege or “blindness,” but I do not know why this revelation came out as such a shocker for me– after all, the only place I had had phodis at, outside my house, were Goan temples. How could they not be an outcome of Brahminism? The food that I had made so many cherished memories with, was ultimately also the product of an exploitative system. I got a putrid taste in my mouth; I instantly wanted to generate some kind of spontaneous hate for the treasured family staple, but I simply could not muster it. Could my empathy and so-called radical-ness strip me off of my love for the music and food I grew up with, that simply happened to be the culmination of a torturous system?

“One day, I filled my pockets with crisply roasted chaanya and went to school. I was going to sneak off to the back of the school in the break and have myself a feast. All went as planned but a Brahmin friend turned up and asked, 'What's this? Eating alone?' I flushed with embarrassment and mumbled, 'Oh nothing, just some crunchies' for want of a better answer. 'How do they taste?' he asked. 'Come on, give us a taste.' I didn't know what to do. Here I was, about to pollute a Brahmin. What if the village found out? Now he began to plead for some. I gave in, gave him some crunchies.

It wasn't that I had some agenda; that I wanted to pollute my high-born friends. It was all innocent, childish fun. And later I would realize that my friends had known what they were eating all along but did it all the same.”

Daya Pawar’s Baluta (translated by Jerry Pinto) reveals the complex ties between food and caste

I have a few routes to go down with this thought. First, art is not created in a vacuum. Second, our resistance against Brahminism is way more complex than the redundant “Culture War vs. Class War” dichotomy that Internet leftists keep talking about. Third, not separating art from the artist is a piece of cake when you think about sacrificing your love for an art form, owing to the context it was created in. Sure, we have come to the conclusion that separating the art from the artist is nearly impossible, but what about separating the art from the context it was made in? It is one thing to enjoy and appreciate individual skills- like vocals and instrumentation and flavours and culinary skills-, but is it okay to still enjoy it once you have learned the shattering history behind the said works of art?

I know this article reads like a Savarna sob story so far, and I know not consuming an art form with problematic origins is nowhere near as hard facing lifelong oppression, humiliation, and torment as a caste-oppressed person. But the more I think about it, the more I realise how utterly clueless I am in my personal journey of unlearning social conditioning, and fighting against casteism. When we talk about overthrowing Brahminism, are we talking about rejecting every single thing that Brahminism has birthed? Or are we just aiming to put an end to the very hierarchy, so that all art is accessible to everyone? Even then, all the “art” that we are planning to make accessible to everyone is a part and parcel of this unjust system, so is it not better off destroyed altogether?

The thing is, a lot of art forms in the “elite” sphere are end-products of cultural appropriation of the subaltern; same goes for Brahminism (even Phodis, probably). Jazz, a blend of West African and European musical traditions, went from being the source of recreation for enslaved African-American people, to being indicted as an eternal part of Western elite culture. Likewise, Dasi-attam, a dance performed by the Devadasis of South India, was blatantly appropriated by Savarnas to create the Brahminical art form of Bharat Natyam. Destroying Brahminical forms of art would, in some way, also destroying the tiny existing portion of original art of subjugated communities, no matter how brutally it was appropriated.

Mulling over Western art forms is easier, because at least I’m not a direct participant in their story— simply an outsider, simply a mindless connoisseur. Nina Simone’s music cannot be stripped off of its context. Apart from its practical brilliance, her music is as well-regarded as it is, is because it reflects the turbulent times Black people were going through at the height of racial apartheid and systemic oppression in America. Gil-Scott Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” isn’t just a catchy statement that modern-day rappers like Kendrick Lamar can twist and turn to sell their commercial shows according to their convenience— it was a much needed wake-up call, urging the poor and marginalised to fight against their oppressors, instead of slacking off in front of the television, getting swayed by corporate America’s nefarious media tools.

Does the road-map to liberation pass through destroying these creations altogether, or giving it back to its rightful owners?

A common sentiment regularly echoed in leftist circles is that of “No war but class war.” This sentence usually makes its way while discussing Western society, which is generally seen as a melting pot of cultures, all of them, however, divided by the class hierarchy. Things are different in South Asia— where society is not only marked by class, but also a wholly different problem of caste, which, on one hand, is rooted in a hierarchy, making it a class-like struggle, but also permeates the lifestyle of the individuals within it, making it a harder nut to crack. Brahmins, the chief oppressor-caste group who dominate the hierarchy, have historically introduced the abstract elements of “purity” and “pollution,” differentiating their culture from that of the castes below them, thereby also making it a culture issue. While multiple ethno-linguistic groups thrive in India, the one common denominator among all of them is caste. And while cultural traditions may differ from one another (most Brahmins in both north and south India are strictly vegetarians, but the Bhadralok of West Bengal and the Goud Saraswat Brahmins of Konkan consume seafood regularly), the ideas of “purity” and “sanctity” being innate to “Brahmin culture” are constant.

Furthermore, we cannot ignore that caste is a uniquely Hindu problem, which has only seeped into other religions in South Asia because of proximity and Hindu dominance. Many Dalits across South Asia chose to embrace religions like Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism, only to escape the hellscape that Brahminism is. Dr. Bhimrao “Babasaheb” Ambedkar, the renowned political leader and immensely respected anti-caste figure, hailed from a caste-oppressed Mahar family and suffered casteism all his life. He himself was vocal about rejecting Hinduism, burning the casteist Hindu religious text of Manusmriti, and embracing Neo-Buddhism (Navayana), as an act of resistance against life-long discrimination. Additionally, E. V. Ramasamy “Periyar,” one of the most influential anti-caste radicals of our time, publicly criticised Hinduism, by rejecting Hindu scriptures and breaking idols.

While these acts may come off as proponents of “culture war” on a surface level, it is pertinent to know that these acts are rooted in a resistance against both class-like and culture-like discrimination. I’d go on to say that caste is perhaps the only social distinction that presents culture on a class-like hierarchy. And from the looks of it, it does feel important to entirely erase a hierarchical culture to ensure the complete destruction of this brutal empire. When we talk about culture war being a distraction to class war- which is the only fight that will guarantee liberation-, a lot of us conveniently forget the idea of a third kind of “caste war,” which simply cannot fit into the Western or Soviet model of Communism. Like I said in my last post, South Asian society is significantly different, and it is imperative that the general template of Communism is tweaked better to address issues of both class and caste within it.

So what is the solution to this sprawling problem? Maybe it’s not left solely to a confused individual like me. A systemic issue cannot be “resolved” by one person alone, but I do hope this essay sparked some new questions in your head, prompting you to spring into action. As for me, personally, I have started indulging in related conversations with my peers, who have given me their own understanding of things, which I might compile into an upcoming essay, but for now, I am glad I could successfully eject a recurring dilemma from my mind, and make something constructive out of it.

Book Recommendations:

Baluta- Daya Pawar

Jevha Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti/When I Hid My Caste- Baburao Bagul

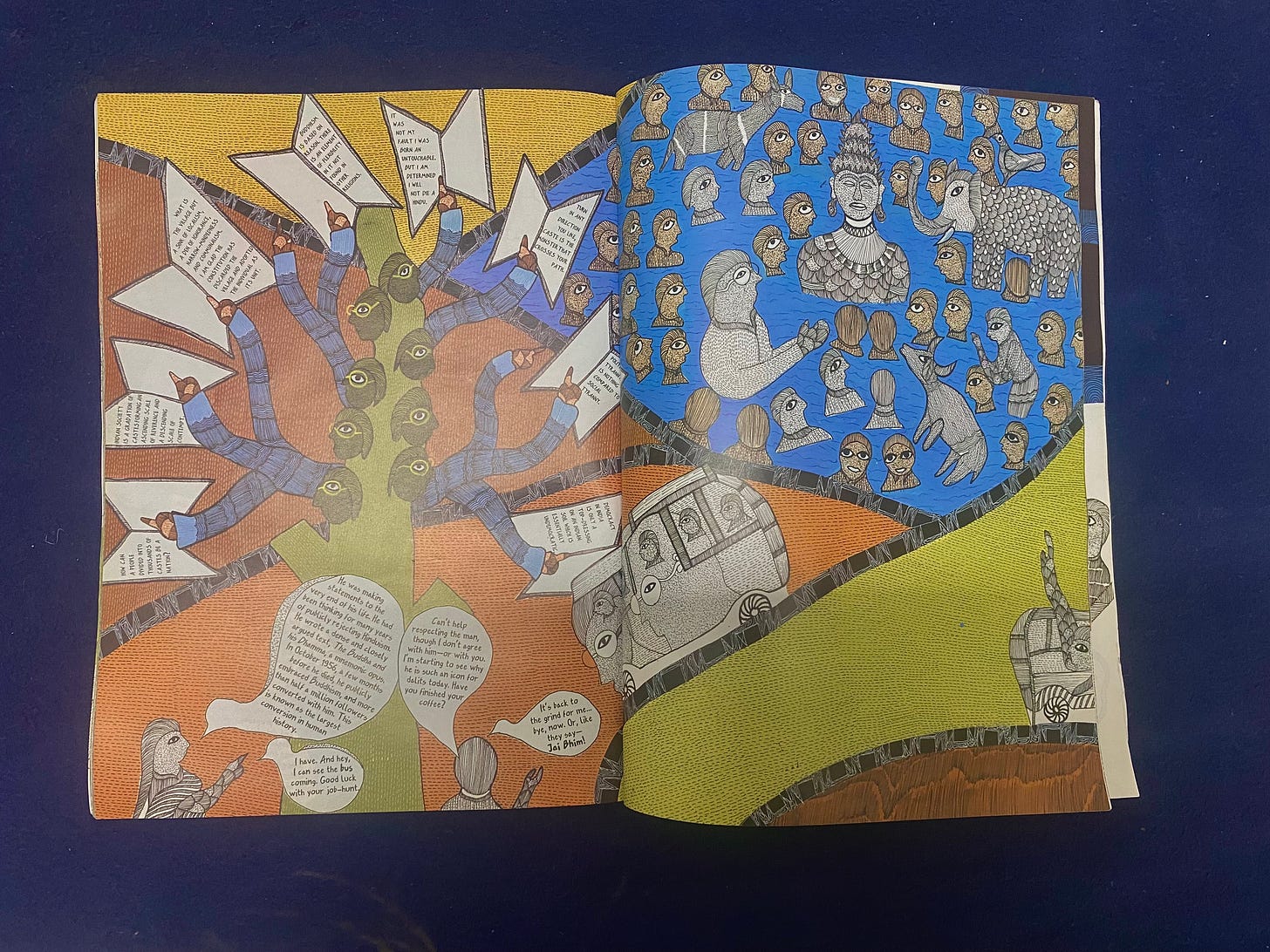

Bhimayana: Incidents in the Life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar

Iconoclast: A Reflective Biography of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar- Anand Teltumbde

I’ve been going back and forth on the idea of a paywall for a minute now. I do not like the concept of a paywall. I’m not judging anyone who has one- I get where you’re coming from and your labour absolutely has to be compensated for- but I feel like that’s just not me. There have been times when I have wanted to read an article only to find out with a dejected face that I need my card and a monetary sacrifice to unlock it. Of course at some point my trajectory of thinking might change as it always has, and I might introduce a paywall, but for now, The Untelevised Revolution is going to remain free for everyone- subscribers and trespassers alike. (Also, putting a paywall with a name like “The Untelevised Revolution”….. yeah.)

THAT BEING SAID, I’m really falling short of money right now and I’m looking at pretty much every option available to help me financially. I know I don’t have a lot of subscribers, but if you did enjoy reading any post of mine at any point and are in the position to help financially, please do so I’d be super grateful to you. To many more.

I say this because I have had non-Hindu Konkani friends tell me that they have had Phodis before, and there are unfortunately not enough resources on the Internet to trace the origins of the dish.

Hey Soniya, I came across your substack via one of your notes and this is the first piece of yours that I've read. I knew what I was getting into based on the title and I also knew that this was going to be uncomfortable. Coming from a "high cast" background myself, I too have been going through the guilt you talk about in this piece. Loved this soo much, even the uncomfortable and awkward parts. Definitely going to read all your pieces asap!

Beautifully crafted, cogent and potent food for thought. Pun not intended.

Have you written or considered writing about how you discovered about caste discrimination, privilege and your own feelings of self blame ? What changed your outlook from mundane, normal, ignorant to self critical, investigate and perhaps even activist ?

I think that there is a good deal to say for you and for us to read and be educated here….